Japan's "Warring States" period was not a good time to be a peasant. Civil war left the country in ruins, its two highest courts were at each other's throats, and, as always, the lower class paid the price. In a house stationed amidst a vast susuki field live the mother (Nobuko Otowa) and wife (Jitsuko Yoshimura) of a farmer who was called off to battle. It's just been the two of them for a while, squeezing out a living by ambushing the occasional samurai and selling off whatever belongings they can. But out of the blue one day comes Hachi (Kei Sato), a neighbor who finally fled from the bloodshed. Slowly, he integrates himself into the womens' self-enclosed world, spurning the mother's advances while enjoying some splendor in the grass with her daughter-in-law. Emotions are mounting as is, but when a wandering warrior with a demonic mask pays the trio a visit, all of the brewing treachery and betrayal comes to a terrifying boil.

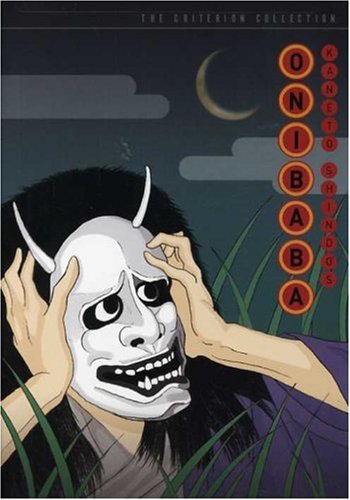

One man, two women, an isolated setting, the air thick with sexual tension -- you'd swear Onibaba was written by Tennessee Williams after a sake bender. But Kaneto Shindo's 1964 picture draws its inspiration from a Buddhist parable, which is enough of an indication that this flick will be playing old-school. Onibaba isn't very steeped in the supernatural (as unlikely as certain scenarios are, they do have basis in reality), but karmic overtones are liberally dispersed throughout. Shindo shows some very bad people doing very bad things, but it's how he goes about displaying his morality that makes the story so fascinating. This isn't so much a battle between good and evil as it one between two different evils -- the farmer's mother doesn't want to lose her partner in crime, and Hachi is just a horny bastard, and in spite of all this, the daughter still grows herself a conscience. It's fair to say Onibaba doesn't sound interesting if a bunch of bickering louts is all we get, but Shindo has us covered by adding a distinctive visual sweep to an otherwise simple story.

While there are several sections in which very little action takes place, Onibaba always has something planned to keep viewers absorbed. The opening scene, which contains no dialogue and lasts around ten minutes, follows two unfortunate samurai who stumble through the susuki reeds and discover the true extent of the dangers war hath wrought. The unknown does present itself when the mother uses her daughter-in-law's fear of religion to scare her away from Hachi, which brings the film's Buddhist origins (not to mention that funky cover art) full circle. These interactions really make the film, thanks in great part to a hell of an on-target ensemble. Otowa projects a hint of innocence (after all, it wasn't her character's first choice to blindside samurai for a living) while she embodies the perfect manipulative spirit. Meanwhile, Sato taps into his inner Toshiro Mifune to play a scoundrel who couldn't be more pleased to be one, and though Yoshimura has a tough time being noticed, she still holds her own and walks away with a solid performance as the closest thing we have to a "good guy."

A bit slow-going at times, Onibaba more than compensates for it with a tale whose emotions draw in your psyche and keep it locked on the action. Emphasis is on art over keeping the plot occupied, but it's to Shindo's credit that he involves you in the proceedings with a minimum of story and many sections that do without spoken words period. The Criterion Collection did well in admitting entrance to Onibaba, a tale whose terrors are no one's fault but our own souls.

No comments:

Post a Comment